PALU – Three meters of mud in Petobo has long dried up, harboring many houses and human remains. Rubble of debris fused in the dust that under the heat.

On the land of the former liquefaction disaster, there are only stories of endless sadness.

The name Petobo became phenomenal after being crushed by the liquefaction on September 28, 2018 ago. The National Disaster Management Agency noted that the 7.4 SR

earthquake triggered liquefaction in 180 hectares of land from 1,040 hectares of the total area of Petobo Village.

The history of Petobo in the folklore of Kaili people. The traditional figure of Pombewe Village, Atman Givu Lando, said that Petobo comes from the word “tobo” which means piercing. The name fits the story of Taboge Bulava who would be marry by a man from Kaili Tara with dowry in making conduit from Kawatuna River.

But during the Petambuli procession, the bridegroom died. Taboge Bulava was later proposed by a man from Panggevei, but was refused by his family.

“This event culminated in a stabbing that injured Taboge Bulava,” Atman said.

Before it was named Petobo, the area was called Jajaki, which meant a place for Polibu or conference, before the war occurrence (kagegere) of Lando – Sidima.

Jajaki area consists of several parts, namely Boya or Ranjole Kinta, Varo, Nambo, Ranjobori, Pantaledoke, Popempenono, and Kaluku Lei.

Nambo before likuefaction, located around Jl. Mamara, Petobo Village. Nambo is taken from the name of King Loru, Nambo Lemba.

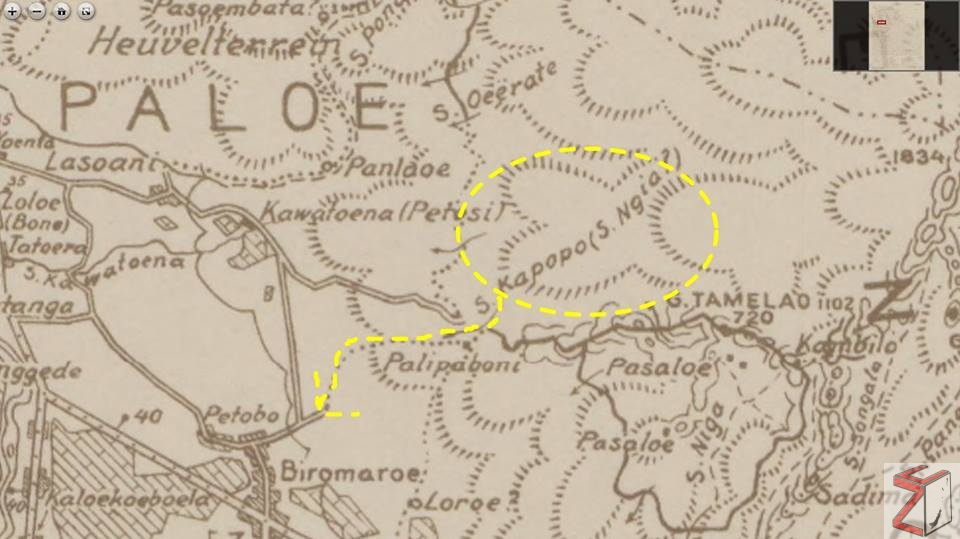

The story of Nambo Lemba ends up missing (na’Lanya) in Ngia River, which used to flow from Kapopo and then meets the Kawatuna river towards Levonu (the area around Dunia Baru and Tatura Mall).

The description of River Ngia was listed in 1897 Map made by Dutch ethnography Albertus Christian Kruyt which published in Batavia Diens Cartography in 1941. It depicted that there was Ngia River (Kapopo) flowing in Petobo.

This is also said by the Central Sulawesi Museum Archaeologist, Muh. Iksam. “It is a former ancient river flows from Kapopo area (new Ngata) and unites with the Palu river in Tatura”.

Atman said, Petobo was only used as a place to fight. That gave rise to the name Pantale Doke, aka the place to put spears and Ranjobori as a special area for warfare.

In the next few years, Petobo was then specifically asked to become a resident. However, in the past, the population of Petobo could not be more than 60 people.

“If more, residents believe there will be disasters and diseases, so that the number will return to 60 people,” Atman said.

In order not to be disastrous, Petobo inhabitants held a traditional ceremony by arranging a number of spears and Guma (swords) to become Kinta or small villages as dwellings.

“Since then the population in Kinta can increase,” said Atman.

In the City Spatial Planning Document of Palu Municipality 1995 was written in that period the land use for settlements and construction of public facilities in the Petobo Urban was only 40,306 hectares.

While the rest is still of shrubs, rice fields, coconut gardens and irrigation.

However, next, Petobo is getting denser with occupancy. Many housing complexes are built on the former of River Ngia.

In that former river, the liquefaction mud on September 28 crushed hundreds of houses and other buildings after the earthquake shook. At the eastern boundary, there

are around 15 houses in Kinta, the first former village in Petobo which survived the liquefaction siege.

The content in this article is published and translated from the Facebook Page of Kabar Sulteng Bangkit

Kabar Sulteng Bangkit is a media to share news about Palu and its surroundings after the natural disaster on September 28, 2018. This page is managed by AJI Indonesia and Internews by involving journalists from AJI Palu.

If you want to contact the editor or provide information regarding post-disaster handling please contact WA: : 0813-4466-5586 or Email: [email protected].